“Rules are mostly made to be broken and are too often for the lazy to hide behind”

– Douglas MacArthur

Grammar is the mortar of the English language we use when building meaning through the use of words, sentences, and paragraphs. For many people, it is such a powerful tool as to be deemed necessary. When we encounter the concept of grammar in school, we are trained to think of it as hard rules.

But just as one may decide to forego brick and mortar when building a house, they may also decide to bend or ignore the rules of grammar. This choice is often divisive, as many readers believe that to forego the rules of grammar is a sign of bad writing or lack of knowledge.

Yet many important works, both old and new, have made this choice. James Joyce famously eschewed tradition in Ulysses (1922) before going even further into experimental territory with Finnegans Wake (1939). Joyce’s works openly flaunt their defiance of grammar, but one can find examples in the works of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, E.E. Cummings, H. L. Mencken, and Lewis Carroll. Personally, I have found great joy in purposefully ignoring the rules of grammar whether it be through prose, poetry, or my series of cut-ups.

While each of these writers have broken the rules, it is only Joyce that truly relishes in it. However, he is far the only one. The following authors are all great influences on my work who absolutely didn’t give a damn about throwing out the old rules if they got in the way. They make my oppositional defiant disorder proud.

William S. Burroughs

William S. Burroughs is by far the most experimental of the writers on our list. In his most famous work, Naked Lunch (1959), he refuses to follow any clear structure. The reader may read the chapters in any order they so desire and still get the full experience. However, for the most part Naked Lunch tends to adhere to the usual grammar rules. The biggest exception to this is his reliance on parentheticals asides.

The works that follow Naked Lunch get far more creative in their disregard of grammar. The Nova Trilogy (comprised of The Soft Machine [1961], Nova Express [1964], and The Ticket That Exploded [1962]) is often referred to as The Cut-Up Trilogy because its use of both the cut-up and fold-in techniques.

A cut-up is created by taking a finished piece of work and cutting it into pieces so that each piece has a few words on it. These pieces are then rearranged to create a new text. Similarly, a fold-in is done by taking two sheets of writing and folding them in half vertically before joining them together. The end result of these techniques can often be quite confusing when approached from the point of view of typical prose. But when you consider them as tone-poems, allowing them to wash over you, I’ve found that they can be highly effective (for an example, see my The Cut-Ups Volume 1: Medicated Death).

While the rules of grammar are often followed in the writing of the original, the end result can’t help but forego them.

José Saramago

The works of Saramago are lyrical masterpieces, though they can be quite intimidating. His books are walls of text. Each paragraph is long and dense. Just looking at them brings to mind the classics like Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (1880) or the work of Proust.

In her introduction to The Collected Novels of José Saramago (2010), Ursula Le Guin highlights Saramago’s radical punctuation: he uses commas instead of periods, making for these epically long sentences; refuses to break his story up into paragraphs (though this is an exaggeration on her part since he does, just not nearly as often as other writers); and the way his dialogue is interwoven into the paragraphs and rarely if ever attributed directly. Le Guin refers to this style as a regression and tells us she dislikes it because it leads to her reading it too fast. As she says, “it [loses] the shape of the sentence and the speech-and-pause rhythm of conversation.”

While Le Guin sees these idiosyncrasies as a detriment, to me it feels like she is failing to engage with Saramago’s novels on their own terms. His use of run-on-sentences create a particular feel that enhances the story. The choice not to designate dialogue firmly plants the characters within the narration of the story, rather than separating them out. When taken as a whole, the end result is a story that feels more in line with a fable or something passed down through oral tradition. There is a timelessness about his works, they feel like they could come from any point in time despite the fact that his primary body of work was composed between 1980 and 2010.

Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh came to prominence with his 1993 novel Trainspotting. Depicting the lives of a handful of Scottish junkies, the novel written in the dialect of each character. Not just the dialogue, but the narration itself. This blend of Scots, Scottish English, and British English is almost feels Shakespearian; at first following along feels impossible until you learn its rhythm and can give yourself over to it. Since it isn’t trying to recreate proper grammar, it tosses the rulebook out the window. In addition to being written in dialect, Welsh also tosses out quotations. Instead speech is destinated by a dash –.

These choices alone would earn Welsh a place on this list, but it is barely scratching the surface of his experimentation. For that we turn to Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995) and Filth (1998).

These choices alone would earn Welsh a place on this list, but it is barely scratching the surface of his experimentation. For that we turn to Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995) and Filth (1998).

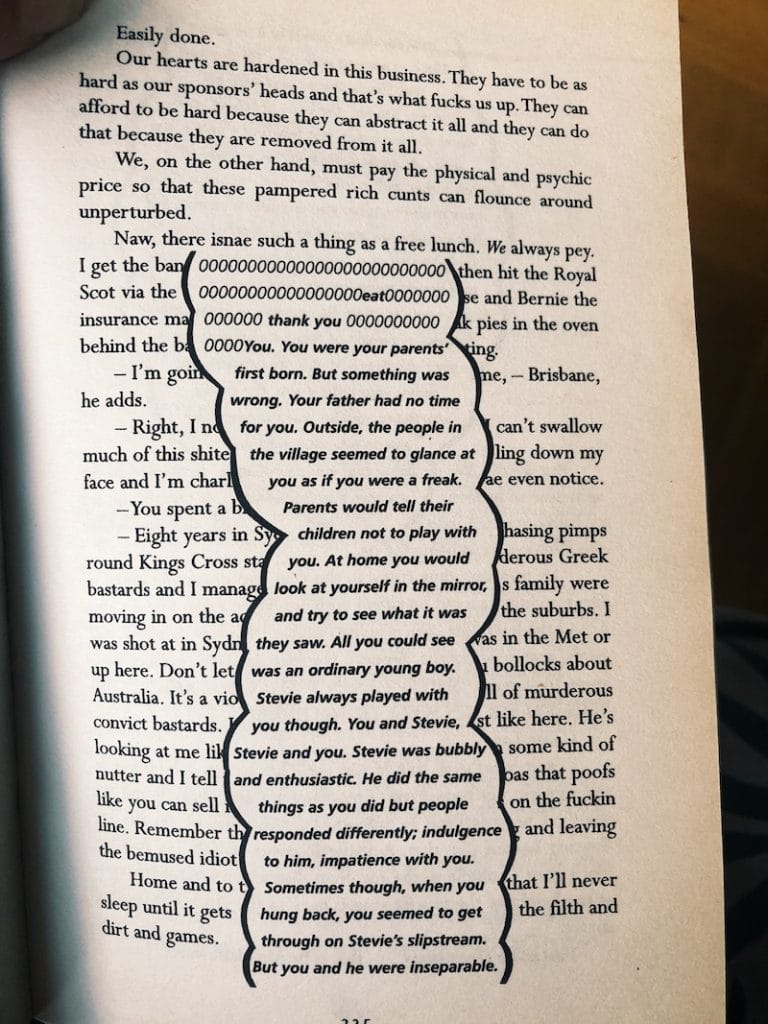

Marabou Stork Nightmares is the story of a man in a coma, almost waking but choosing instead to go deeper into the dreams he is having. It features all of the same odd grammatical choices present in Trainspotting but pushes them even further. Yet it’s most interesting feature is the way it depicts the protagonist on the border of waking up. Text will start to lift up up, representing the character being pulled out of his dream towards consciousness, as the above excerpt shows.

Establishing a pattern, Filth takes things a step further. In this novel about a corrupt cop, the protagonist happens to be host to a tapeworm that has begun to develop a consciousness of its own. That consciousness makes itself known by intruding upon the book, literally taking over whole pages and pushing the narrator out of the spotlight to share its developing views. It’s one of the most audacious things I’ve ever witnessed in a novel.

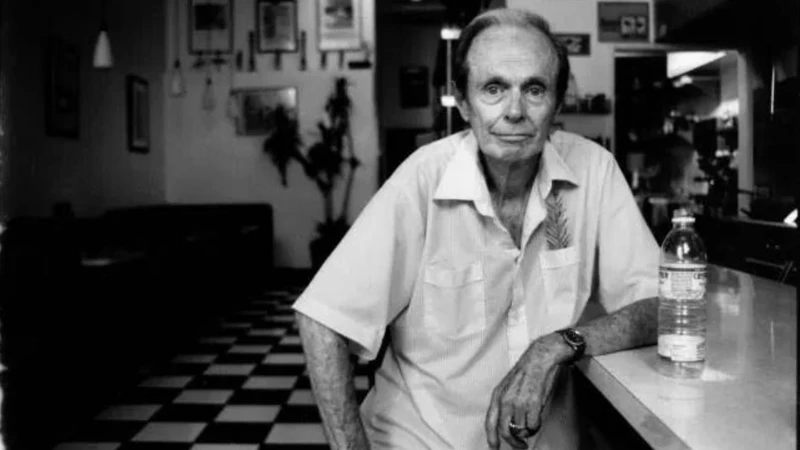

Hubert Selby, Jr

Of the four author’s we’ve looked at, Selby’s work is by far the most consistently experimental. Burroughs’ work might get more esoteric by the nature of the cut-up or fold-in technique, but it is clear that the man understands what he is doing when looking at his earlier works like Junkie (1953) or his later works like Cities of the Red Night (1981). Glancing through a Selby novel, you might not be so convinced.

Selby’s style gives absolutely no concern to grammar. He by far one of the most unorthodox novelists of all time. Writing in a stream-of-consciousness style, Selby often alters his prose to fit the emotional landscape of his characters. Take a look at his story Tralala from Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964). The story follows a prostitute whose stuck in a fast life, picking up drunken sailors to earn enough to afford her next beer. Across twenty-one pages, we never get a single paragraph break. This choice leaves the reader with nowhere to “escape” to. There is no moment where we can sit back and take a deserved breath. We are as stuck in Tralala’s life as she is.

Selby uses a similar technique in many of his stories, but perhaps none do it as well as The Demon (1976). This was my introduction to Selby’s writing and still my favorite of his works. It concerns a man named Harry White who can’t escape his need to sin. As the book progresses, Harry commits horrendous acts in a doomed attempt to clear his head. By the end of the book, Harry decides to commit the worst sin he can imagine. Selby’s use of language in capturing this event makes it feel, paradoxically, like both the quickest and slowest moment. He achieves this by placing the event inside of a single sentence, but having that sentence span several pages. This choice means that as Harry physically flees the scene of the crime, we the reader are dragging it with us because Selby has kept the sentence going. It’s easily one of my favorite moments in literature and you can find tribute paid to it in both More Precious Than Jewels and A Speck of Paint.

We would be remiss if we ignored Selby’s use of “spontaneous prose,” the term Jack Kerouac used for his own stream-of-consciousness works like On The Road (1957). Kerouac believed that the best thing a writer could do was get it down as quickly as possible, avoiding edits. One of the components that Kerouac cared about deeply was the idea of breath. He often choose to skip periods, since they signaled a point to pause for breath, instead choosing dashes that connect multiple phrases together. If anybody could be said to be the heir apparent to Kerouac’s spontaneous prose, it could only be Selby.

Selby wrote as quickly as possible. He ignored quotation marks and often skipped attribution of dialogue entirely to instead work it into the paragraphs naturally. He would indent new paragraphs wherever he liked, often simply skipping down to the next line to start the new paragraph where the old one left off. The thought here being that resetting the typewriter was just another way of slowing down the writing process. Likewise, he choose to use slashes instead of apostrophes because it took less time on a typewriter.

These choices can seem arbitrary, messy, pointless. Upon discovering Selby for the first time, it is easy to think he doesn’t know how to write. Yet all it takes is to read one of his stories to understand why he spent the last twenty years of his life teaching creative writing in the Master of Professional Writing program at the University of Southern California. His style may seem sloppy, but is actually the result of a lot of hard work and experimentation.

Selby, like the other authors on this list, knew the real secret behind writing. Grammar is only necessary when it aids the writing in question. Anything is permissible, so long as it strengthens the story.

Discover more from Writing Darkness

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.