The mystery genre can largely be divided into three categories:

Who did it?, How do it?, and Why do it?

Each category requires the author or filmmaker to hide certain information from the audience:

-

-

- Se7en (1995) hides the who but gives the how and why.

- In Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970) we know who did the crime but it takes some time before we find out why.

- Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997) manages to hide all three, especially how the core crime is committed.

-

Mystery stories hide information in order to more deeply engage the reader/viewer by inviting them to solve the mystery before the characters. There would be no mystery without first hiding some information from us. While it is a vital part of the genre, this technique is not limited to mysteries.

Obfuscation is a powerful tool that should be in every creative’s ‘toolbox.’ In the following examples we will learn four ways of obscuring information that could be used in any genre.

Eliminating the Unnecessary

Whenever we write, we are making a decision about what we reveal and how much of it to show. This means we’re often actually hiding quite a bit from the audience.

I write “Dave made a sandwich.” This sentence conveys enough for you to understand the action that is occurring and create a picture of it in your head. Yet it hides the type of sandwich, whether it was white or brown bread, what condiments he selected, etc. These details could make for a stronger image, though often information like this is simply unnecessary.

The horror genre does this quite often. In Mrs. Tinkles I wrote, “She made it two steps forward before something in the darkness bit off her big toe.” There’s no elaboration on the dismemberment of the toe: the flesh pulling apart in ribbons, the sinews tearing free of the bone. There’s two reasons for this. The first is that I want the moment to suddenly wash over you out of nowhere and that means it needs to happen in as few words as possible. The second is that I trust in your brain’s ability to conjure the image in horrific detail.

The horror genre does this quite often. In Mrs. Tinkles I wrote, “She made it two steps forward before something in the darkness bit off her big toe.” There’s no elaboration on the dismemberment of the toe: the flesh pulling apart in ribbons, the sinews tearing free of the bone. There’s two reasons for this. The first is that I want the moment to suddenly wash over you out of nowhere and that means it needs to happen in as few words as possible. The second is that I trust in your brain’s ability to conjure the image in horrific detail.

Increasing Suspense

There’s a moment that occurs quite often in Japanese horror films, especially those made during the late 90s / early 2000s boom. As a big reveal happens, the camera lingers on the protagonist’s face and we see them react to the horror they are witnessing. Only after several beats does the film cut to reveal what they are seeing. Unlike most American films, this moment is not used to set up a jump scare. In J-horror, this technique is used to increase the suspense.

I recently read Ryū Murakami’s novel From the Fatherland, with Love and saw how he achieves a similar effect in prose. There’s a moment in the middle where a firefight is about to occur because the government is taking a military leader hostage. The chapter leads up as close as possible to the battle… and then ends. When the next chapter starts, there is no battle. We’ve jumped forward a day, so everything has already occurred. As a reader, you are desperate for more information and this state of suspense lingers, making it impossible to put the book down until you get the answer.

It’s very effective in building suspense, but it also achieves another effect that is unrelated but worth mentioning. Each chapter is told from the perspective of a different character and the one following the cliffhanger jumps to a character that witnessed the battle. This allows Murakami to present the battle to us as his memories, so we get answers to the questions we were left with. But it also shows us how witnessing such violence affects those who are unaccustomed to it, instead of presenting through the perspective of somebody used to it.

Maintaining Tone

I recently discovered 1998’s The Boys, an Australian crime film inspired by a horrendous murder that occurred in 1986 wherein the victim was first tortured and violated before being left to bleed to death. You’d probably assume from this that the movie is quite bloody and brutal.

The film actually has very little violence in it thanks to the choice to set the film about twenty-four hours before the murder happens. We spend the runtime watching how three brothers work themselves up into a state where some kind of horrific crime was unavoidable. We only see the victim in the last minutes of the movie, cutting to credits at the moment our characters decide to approach.

By choosing to entirely remove the murder from the movie, the film benefits in two key ways. The first is that this focuses attention on the social aspects that give rise to the murder, rather than becoming a gorefest by focusing on the murder. Secondly, this prevents the film from getting too dark. If the film ended by depicting the murder it would overpower the rest of the movie and take away from the character study it is performing.

The Boys is an uncomfortable watch, but it would be truly miserable if it depicted the murder. The same can be said about 2022’s The Coffee Table, a film so dark many people don’t realize it’s a comedy. It’s the bleakest of comedies, certainly. It asks the question “What’s the worst thing that could happen by buying a coffee table?” I won’t spoil the answer to that question, except to say that we never see it occur. We deal with the aftermath. If you have seen the movie, or inferred the answer from the trailer, then you know just what a terrible time it would be if the movie depicted its key event.

Some things are too powerful. Once shown, they hang over everything else and change the story’s tone. An example of this from my own work occurs in The Kid and the Cat. I leave the horrific event at the core of that narrative up to your imagination. I do this for two reasons. The first is that showing the event in question would make the story even more dour than it already is. The second reason is for…

Focus

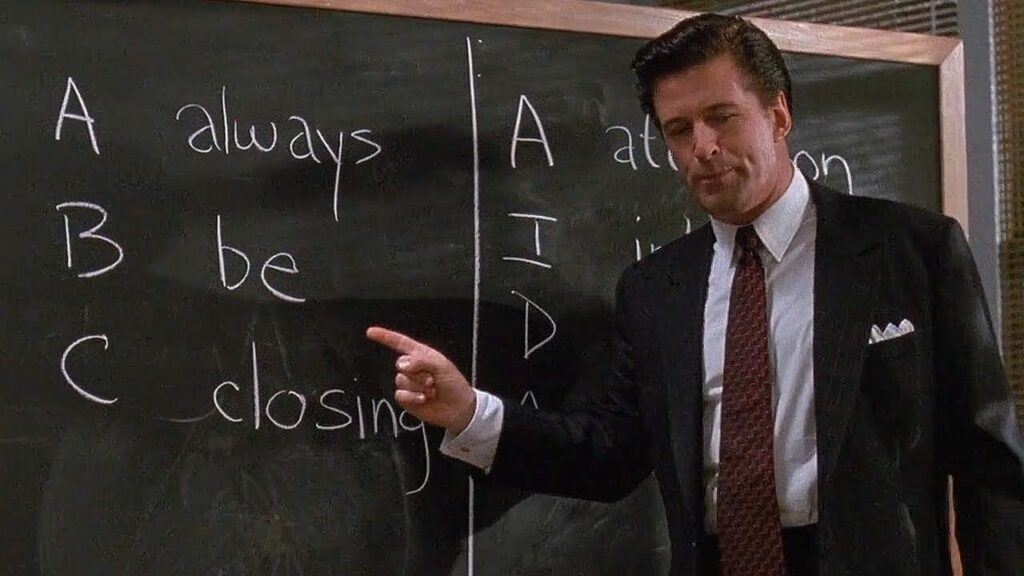

In Reservoir Dogs (1992) a jewel heist has gone horrible wrong. We spend the movie in a warehouse where the criminals have gone to lay low and regroup. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) is set in the world of real-estate salesmen and revolves partially around the potential theft of fresh leads (information that could lead to sales).

In Reservoir Dogs (1992) a jewel heist has gone horrible wrong. We spend the movie in a warehouse where the criminals have gone to lay low and regroup. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) is set in the world of real-estate salesmen and revolves partially around the potential theft of fresh leads (information that could lead to sales).

Where Reservoir Dogs is violent, Glengarry Glen Ross is reserved. But for all their differences, the movies both choose not to depict the crime that occurs. This creates a mystery around what happened, though generating a mystery is almost a secondary concern. What obscuring the crime does is allow the audience to focus their attention on what matters: the characters.

In these films, the crime is not important. The fact that there was a crime is what matter. We’re watching how people react after a crime has gone wrong.

When we tell stories, it is always tempting to add everything we possible can. But quite often our stories are strengthened by removing the pieces that distract from our goal: telling a damn fine tale.

Discover more from Writing Darkness

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.